The desire to experience an adventure is growing more and more. Next to that the worldwide transportation network expands, resulting in more people looking for extreme experiences every year. In addition, the average age of adventurers increase and they tend to have a medical condition more often. Today’s doctor is consulted more frequently by these middle aged thrillseekers with questions about the (medical) preparation to be undertaken, taking into account their personal medical history. These old folks may be medically well under control at sea level, this can change when they expose themselves to high, low-oxygen environments. We know that some conditions can change at altitude, but little is known about many other conditions. In January ‘22, Andrew Luks and Peter Hackett published in ‘The New England Journal of Medicine’ a nice overview of the challenges this phenomenon entails, focused on altitude medicine.

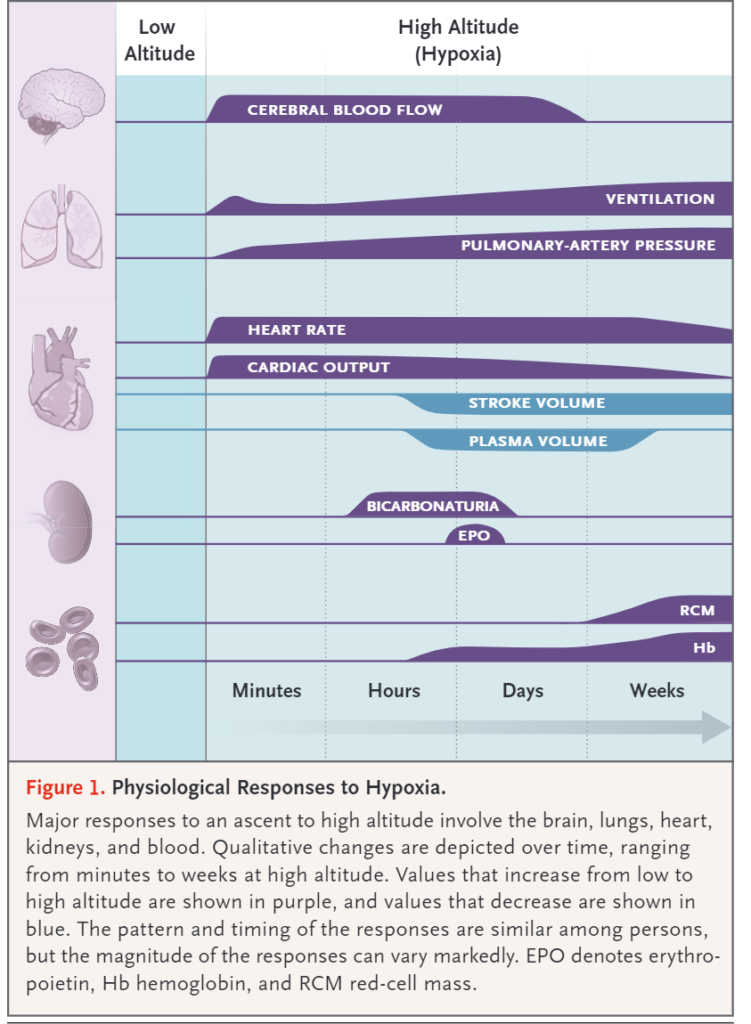

At altitude a body needs time to acclimatize. The lower atmospheric pressure causes a lower partial pressure of oxygen (PO2), triggering a combination of physiological processes to maintain the highest possible oxygen concentration in our organs: ventilation increases, stroke volume increases, cerebral perfusion increases etc. Some processes peak immediately, but others reach their optimal effect only after a few weeks, such as the increase in hemoglobin concentration. The magnitude of most reactions depends on the degree of hypoxia a person is exposed to and can also vary considerably from person to person.

If someone does not take enough time for acclimatization or is not able to acclimatize properly, this can become a problem. For healthy people there is a risk of developing some form of altitude sickness from 2000m, especially if they ascend too quickly. In some patients symptoms may develop at a lower altitude if they suffer from an illness that prevents the person from acclimatizing optimally.

When you as a doctor are being confronted by a patient with the question whether he can safely hike the Annapurna circuit (maximum cruising altitude of more than 5400m), you will not find specific advice for most conditions in the available literature. In that case, Luks and Hackett say, you should think of the advice yourself with the following four questions. These questions help to estimate the amount of risk the traveller will be exposed to. The first three questions focus on assessing the patient’s ability to acclimatize. The fourth question concerns the risk of progression or a complication of the underlying condition.

- Is the traveller at risk of developing severe hypoxemia by traveling to altitude? This may be the case in patients with pre-existing hypoxemia, such as patients with COPD, interstitial lung disease, cystic fibrosis or cyanotic congenital heart disease.

- Does the traveler have sufficient capacity to generate an adequate hypoxic ventilatory response? In other words; are they physically able to increase their ventilation in an oxygen-depleted environment? This includes patients who do not have the neuromuscular capacity to increase ventilation, such as patients with very severe COPD, neuromuscular disease or the obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Other patients are unable to generate an adequate response due to impaired function of the carotid chemoreceptors. So they are not triggered by hypoxemia. This includes patients who have had surgery on the carotid artery(s) or those who have received radiotherapy in this area.

- Is the patient at risk due to impaired pulmonary arteries? Alveolar hypoxia induces hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, which leads to increased pressure in the pulmonary artery. This can lead to problems in patients who already have elevated pressures, such as pulmonary hypertension or right-sided heart failure. An increase in pulmonary pressure may result in HAPE or progression of congestive heart failure.

- Can hypoxia cause complications or progression of the underlying condition, such as sickle cell disease or coronary artery disease?

Luks and Hackett provide a nice overview in the article with advice for several illnesses. You will also find absolute contraindications for traveling to altitude. In case of relative contraindications it is possible to consider taking additional measures. For example one can choose to bring extra oxygen or one can start pre-acclimatization at home by sleeping in an hypoxic tent.

Travelers should be aware of the medical problems that may arise. It is useful to know which medical facilities are nearby and whether it is easy to descend quickly. Tell the patient to inform the expedition leader about his medical situation. Be cautious with diseases that are prone to have exacerbations. This patient’s condition should be well under control. Also prepare an emergency plan in case an exacerbation does occur. In addition, medical equipment can function less well under extreme conditions. Doses from inhalers can change due to altitude, glucose meters can malfunction, liquid medication such as insulin can be affected by the cold and/or low air pressure etc.

Finally, in the prevention and treatment of altitude sickness with medications, the patient’s history should be taken into account. The commonly used drugs acetazolamide and dexamethasone each have their contraindications and interactions. For example, with dexamethasone you should be alert for hyperglycaemia and with acetazolamide in combination with a loop diuretic for hypokalaemia.

It is good to know that many medical conditions do not have to impede an adventure at altitude. Much is possible with the right preparation. And if, despite all the good preparations, everything still goes wrong: returning back to sea level as quickly as possible is the best medicine!

This text is an edit of the article ‘Medical Conditions and High-Altitude Travel‘, Luks en Hackket, The New England Journal of Medicine, 2022. You can find the full article here

Want to learn more about altitude medicine? Check out the course Mountain Medicine

Looking for (remote) medical advice for your own expedition? Click here