Stijn Thoolen has been selected by the European Space Agency (ESA) to conduct research at Concordia, Antarctica from November 2019 up to and including the beginning of 2021. We occasionally receive an update from Stijn about his findings on this small, isolated part of the world. Today the sixth piece, where he tells us his first winterover experiences on Antarctica, isolated from the rest of the world, and the COVID-19 outbreak.

Concordia, April 7, 2020

Sunlight: about 10 hours

Windchill temperature: -72°C

Mood: just fine

It is quite strange to be here, on the only continent not affected by the corona virus. To me, with everything that is currently going on in the rest of the world, it makes feel even more distant than we already are. Here life just goes on, and although it has not been easy for some of us either, not being able to share in these experiences or provide support at home to those who could use it, messages are now suggesting that we are suddenly the ones better off!

And I have to admit indeed. Even though we are stuck here for nine months without any possibility for evacuation, with limited resources, a disrupted work/leisure balance, a threatening environment outside, both environmental and social monotony, and a group of relative strangers that come from all sorts of backgrounds (reading this I guess the situation for you may perhaps not be so different), at least we came here by choice…

So let me start with saying that I really hope you are doing well. Being isolated and confined comes with all kinds of stressors, deviations from the normal situation you could say, that ask our body and mind to adapt. Given the sudden disruption that the Corona outbreak has caused to all of you, I imagine that is certainly not easy.

And while our experiences are so different, and even though I feel probably as ignorant as you about how to deal with all those stressors (we have just been left to ourselves two months ago), perhaps this is a good time to share with you some of my own thoughts about isolation at Concordia.

A while ago I came across a story about the 1897-1899 Belgian Antarctic Expedition, which I found quite illustrative for what I have considered to make my winterover a happy one this year. At the time the Antarctic was still mostly unknown territory. The south pole was not yet reached, and the unforgiving environment made many expeditions end in disappointment. Aimed for exploration and for science, this one was no exception. When their ship the Belgica got stuck in the pack ice of the Bellingshausen Sea, the 19-member crew became the first in human history to winterover below the Antarctic circle, and as such you can imagine they were badly prepared to do so. It must have been pretty difficult, I imagine. Expedition doctor Frederick Cook described depression, irritability, headaches and sleeplessness among the crew, and basically provided a first recorded description of the so-called ‘winterover syndrome’.

“The curtain of blackness which has fallen over the outer world of icy desolation has also descended upon the inner world of our souls” – Frederick A. Cook, 1900

The strange and extreme Antarctic environment, just like in space, indeed has a strong capability to upset our system. Symptoms like fatigue, headaches, sleep disturbances, impaired cognition, negative emotions such as depression, anxiety and anger, and interpersonal conflicts have all been observed in polar dwellers. Such symptoms are usually more prevalent during the harsh winter months, when stressors are highest. Hence the ‘winterover syndrome’. For the winterover crew of 1898, Dr. Cook reasoned that what they needed that was the opposite of that harsh winter environment. Apparently with good effect, he prescribed them a diet of milk, fresh meat (poor penguins) and cranberry juice, as well as exercise, warmth and light. Interesting I think, not necessarily his particular ‘baking treatment’ of having the crew sit naked around an open fire, but the way it shows how dependent we are on our environment, and our limitations to adapt. In other words, to facilitate adaptation, we may want to create an environment that is more familiar to us.

For here in Concordia, or perhaps for something as different and unexpected as a Covid-19 lockdown, I like to think the idea is quite similar. I therefore try to maintain a daily rhythm full of activities that mimic a little bit the world we come from. I try to wake up and go to bed at regular times to promote sleep and maintain a functioning biological clock (without sunlight it relies even more on social clues), and while I restrict myself as much as possible from bright computer screens in the evening hours, an artificial daylight is standing by in my office for the darkest months. Elisa, our cook, is making us pretty balanced meals twice a day, and even though I have to admit I eat a lot here (altitude plus cold equals many burned calories), I take vitamin D in addition to make up for the lack of sunlight. About three times a week I visit the gym (it got a little too cold outside) to stimulate myself physically, and if not working, sleeping, eating, or exercising, I try to stimulate my senses by an impact from the magnificent world outside, playing games together, or reading a book. Socially, I try to stay connected with my friends and family at home, and with the crew we regularly have video connections with schools for outreach purposes, and even with each other’s families. We are social beings after all, and we may easily become lonely if we don’t feel part of the group (whichever group that may be…). Finally, to relieve some of the excess amount of stress here, I try to practice meditation each morning, and for the same reasons we have our sauna (yes, sauna) open on Sunday’s. Perhaps it really is a paradise…

But while I like to believe that maintaining such a routine may already give us a handful of things to distract us from boredom and unfilled time (which is perhaps more stressful than no time), I wonder if it will be enough to get us through those nine monotonous months. At home, the world around us is constantly changing, providing us with new input every day. New people, new weather, new smells, new tastes, new projects, new whatever. Rather than just routine, such novelty may be as important to prevent us from being under-stimulated. It may require a bit of creativity though…

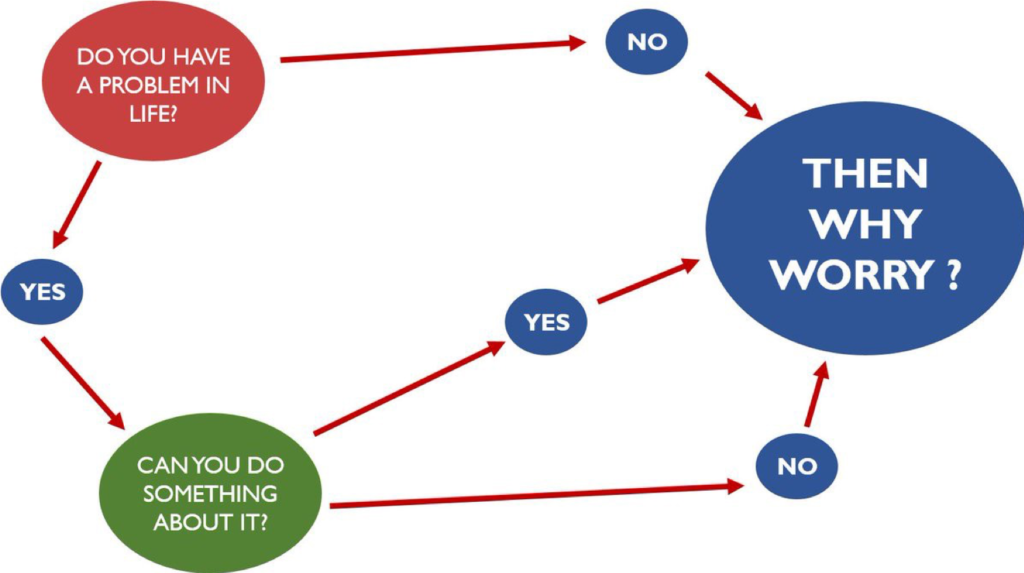

Doing all these things that you may not be used to do at home is not always easy, and from a psychological point of view (and that is where I believe you can really make a difference), it requires effort. Sometimes you may want to act in a way that seems beneficial to you, but actually has an opposite effect on the long term (I think we all recognize that idea, not?). For me, this is perhaps the biggest challenge this year: to be able to maintain my motivation to bring up that discipline, to see that ‘bigger picture’, and be able to understand what brought me here in the first place, especially when exposed to those winter stressors. Those are the moments we tend to become more self-oriented, and lose our perspective to the world outside.

Perhaps that is also the main reason for interpersonal conflict to occur so often during polar expeditions. Differences in gender, occupation, interests, opinions: all of them may become an irritant if we forget that we are not all like ourselves. Knowing that such relational problems are among the greatest stressors for winteroverers (so indeed we are social beings after all), we better bring up the discipline to maintain that flexibility and tolerance for each other. Here more than anywhere else we need to actively maintain our relationships by respecting communal tasks and privacy, and mood variations and different opinions. And perhaps those awkward communication and team bonding exercises during pre-departure training weren’t so stupid after all, rather helping us in that effort to understand each other’s actions and intentions. Acting against our instincts may be difficult sometimes, but in that self-control, or self-improvement rather, I see my individual moral responsibility this year.

It is certainly not going to be an easy year, and we still have many months to go. It will ask a lot of flexibility to deal with its strangeness, deprivations, and stresses. But as I have mentioned in a previous blog post, I like to think that it has its positive sides as well. Often seen in Antarctic winterover expeditions, sharing and overcoming such challenges may fill us with a sense of accomplishment, increased self-esteem, larger problem-solving capabilities, and social proximity to others (how contradicting that now may sound…). Being taken out of the comfort of our daily routine may give us an opportunity to see the precious things that we usually like to take for granted. It can show us how much we depend on each other, and how vulnerable we can be. To me, that is a very valuable experience.

So maybe we can imagine we are all polar dwellers these days, or astronauts if you prefer. While I wish that the damages done by the Corona virus will soon come to an halt, and that everyone is able to overcome their personal challenges, I can only hope that the current lockdown experience will one day bring you something that we can share after all. That sense of humility, we could then call perhaps the ‘Corona-over syndrome’.

And, in case being locked inside is making you feel as corny as our conversations here at the dinner table, this may be the right song to end this blog in style: LEGO Movie 2 – Everything’s Not Awesome

On behalf of the DC16 crew here at Concordia, even though we are thousands of kilometers away, we are close to you in thought!